The Gruesome Story of Phineas Gage: How a Severe Work-Place Accident Influenced Neuroscience and Theory of Frontal Lobe Function

- May 15, 2016

- Posted by: Administrator

- Category: Psychology Explained,

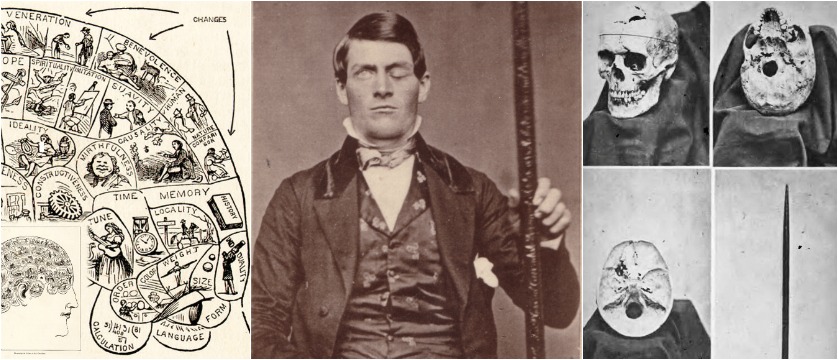

In 1848, in what was truly one of the worst “bads day at work” in recorded history, twenty-five-year-old railroad construction foreman Phineas Gage was packing powder and sand into a hole in rock when the powder detonated.

The result? A 13-pound iron rod was driven through his cheek, out of the top of his head to land 30-some yards behind him. One of the more amazing anecdotes of this event was that Phineas was brought to town–conscious–and he sat on his porch relating the details of the accident to his landlord while a doctor was summoned from the next town.

The Damage

Although he suffered an infection soon after, and his family prepared a coffin for him, he soon recovered, even though the rod damaged one or both of his brain’s frontal lobes.

A report on Gage’s brain injuries, published by his physician Dr. Harlow a few years later in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Medical Society, indicated the accident had completely altered his personality and behavior.

His friends described him as “no longer Gage.” In fact, even though he was physically capable of doing his former job, he was fired because he no longer worked well with others.

Gage’s story proved to be popular and captivating around the world. After the report was published, a subsequent poem described the results of the accident:

“A moral man, Phineas Gage,

“A moral man, Phineas Gage,

Tamping powder down holes for his wage,

Blew the last of his probes

Through his two frontal lobes;

Now he drinks, swears, and flies in a rage.”

Correcting Misinformation

Until this report was published in 1868, Gage’s accident was used to prove that the cerebral hemispheres had no relation to intellectual function. In fact, it’s suggested that his doctor intentionally withheld information about his personality change.

His doctor’s report was significant because it correlated other neurologists’ reports of the effects of specific brain lesions on behavior. After all, at the time, phrenology was very popular.

Developed in the late 1790s, phrenology proposed that the personality traits of a person can be discerned from the shape of the skull. Gage’s accident proved phrenology wrong.

The Reality

While Gage’s case has no doubt been fascinating for the last 150 years, although he survived the accident, his life was forever altered by the severe brain injury. After losing his job, he later found work in a livery, eventually moving to Chile to pursue this occupation.

By 1859, he was feeling unwell and returned to the US to live with his mother and sister. Within a few months, he began to suffer a series of increasingly severe convulsions, dying in May 1860 at only 37 years old.

It depends on who you ask to determine just how important Gage’s story is to the field of neuroscience. His version of the case was used by David Ferrier as the keystone in the first modern theory of frontal lobe function.

However, a survey of published accounts has found that modern scientific presentations of Gage’s story are usually distorted—they exaggerate and even directly contradict the established facts.

However, most authors now agree that the most important fact to arise from his ordeal was that surgery could be performed on the brain without automatically leading to death.

References

- Cyber Museum of Neurosurgery — Retrieved 7 April 2010

- Macmillan, Malcolm (2000). An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage.Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Fleishman, John (2004). Phineas Gage: A Gruesome But True Story about Brain Science. San Anselmo, CA: Sandpiper Press.

- The Phineas Gage Information Page — Retrieved 7 April 2010

- Ratiu P, Talos IF. (2004) N Engl J Med 351: e21. Images in clinical medicine. The tale of Phineas Gage, digitally remastered.

- Damasio H, Grabowski T, Frank R, Galaburda AM, Damasio AR. (1994) The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient.Science 264: 1102—1105.

- Lukic IK, Gluncic V, Ivkic G, Hubenstorf M, Marusic A. (2003) Virtual dissection: a lesson from the 18th century. Lancet 362: 2110—2113.